![]()

![]()

Welcome to the second part of the reworked "Linux Fundamentals" series. We'll be applying our knowledge from the first installment in this series, so I highly recommend you completing that room before proceeding further.

In part 2, we'll be ditching the in-browser functionality and help you get started in what is a fundamental skill in being able to login to and control the terminals of remote machines. Not only this, but the room will also have you:

- Unlocking the potential of your first few commands by introducing you to using flags and arguments

- Advancing your knowledge of the filesystem to perform some more useful commands such as copying and moving files

- Introducing you to the access mechanisms in place to keep files and folders secure and how to identify the things that our current user has access too

- Running your first few scripts and executables!

The in-browser functionality was used in Linux Fundamentals Part 1 to get you directly connected to your first ever Linux machine without any hassle.

In fact, the in-browser functionality uses the exact same protocol that we are going to be using today. This protocol is called Secure Shell or SSH for short and is the common means of connecting to and interacting with the command line of a remote Linux machine.

We will be deploying two machines in this room:

- Your Linux machine

- The TryHackMe AttackBox

What is SSH & how Does it Work?

Secure Shell or SSH simply is a protocol between devices in an encrypted form. Using cryptography, any input we send in a human-readable format is encrypted for travelling over a network -- where it is then unencrypted once it reaches the remote machine, such as in the diagram below.

You can learn about the various types of encryption on a TryHackMe room. But for now, we only need to understand that:

- SSH allows us to remotely execute commands on another device remotely.

- Any data sent between the devices is encrypted when it is sent over a network such as the Internet

Deploying Your Linux Machine

Deploying the TryHackMe AttackBox

Using SSH to Login to Your Linux Machine

The syntax to use SSH is very simple. We only need to provide two things:

1. The IP address of the remote machine

2. Correct credentials to a valid account to login with on the remote machine

For

this room, we will be logging in as "tryhackme", whose password is

"tryhackme" without the quotation ("") marks. Let's use the IP address

of the machine displayed in the card at the top of the room as the IP

address and this user, to construct a command to log in to the remote

machine using SSH. The command to do so is ssh and then the username of the account, @ the IP address of the machine.

But first, we need to open a terminal on the TryHackMe AttackBox. There is an icon placed on the desktop named "Terminal". And now, we can proceed to input commands.

For example: ssh tryhackme@MACHINE_IP .

Replacing the IP address with the IP address for your Linux target

machine. Once executed, we will then be asked to trust the host and then

provide a password for the "tryhackme" account, which is also "tryhackme".

Now that we are connected, any commands that we execute will now execute on the remote machine -- not our own.

A majority of commands allow for arguments to be provided. These arguments are identified by a hyphen and a certain keyword known as flags or switches.

We'll later discuss how we can identify what commands allow for arguments to be provided and understanding what these do exactly.

When using a command, unless otherwise specified, it will perform its default behaviour. For example, ls lists

the contents of the working directory. However, hidden files are not

shown. We can use flags and switches to extend the behaviour of

commands.

Using our ls example, ls informs us that there is only one folder named "folder1" as highlighted in the screenshot below. Note

that the contents in the screenshots below are only examples and are

not those of those the instance that you deploy in this room.

However, after using the -a argument (short for --all), we now suddenly have an output with a few more files and folders such as ".hiddenfolder". Files and folders with "." are hidden files.

Commands that accept these will also have a --help

option. This option will list the possible options that the command

accepts, provide a brief description and example of how to use it.

This option is, in fact, a formatted output of what is called the man page (short for manual), which contains documentation for Linux commands and applications.

The Man(ual) Page

The manual pages are a great source of information for both system commands and applications available on both a Linux machine, which is accessible on the machine itself and online.

To access this documentation, we can use the man command and then provide the command we want to read the documentation for. Using our ls example, we would use man ls to view the manual pages for ls like so:

What directional arrow key would we use to navigate down the manual page?

What flag would we use to display the output in a "human-readable" way?

We covered some of the

most fundamental commands when interacting with the filesystem on the

Linux machine. For example, we covered how to list and find the contents

of folders using ls and find and navigating the filesystem using cd.

In this task, we're going to learn some more commands for interacting with the filesystem to allow us to:

- create files and folders

- move files and folders

- delete files and folders

More specifically, the following commands:

| Command | Full Name | Purpose |

| touch | touch | Create file |

| mkdir | make directory | Create a folder |

| cp | copy | Copy a file or folder |

| mv | move | Move a file or folder |

| rm | remove | Remove a file or folder |

| file | file | Determine the type of a file |

Protip: Similarly to using cat, we can provide full file paths, i.e. directory1/directory2/note for all of these commands

Creating Files and Folders (touch, mkdir)

Creating

files and folders on Linux is a simple process. First, we'll cover

creating a file. The touch command takes exactly one argument -- the

name we want to give the file we create. For example, we can create the

file "note" by using touch note. It's worth noting that

touch simply creates a blank file. You would need to use commands like

echo or text editors such as nano to add content to the blank file.

This is a similar process for making a folder, which just involves using the mkdir

command and again providing the name that we want to assign to the

directory. For example, creating the directory "mydirectory" using mkdir mydirectory.

Removing Files and Folders (rm)

rm is extraordinary out of the commands that we've covered so far. You can simply remove files by using rm. However, you need to provide the -R switch alongside the name of the directory you wish to remove.

Copying and Moving Files and Folders (cp, mv)

Copying and moving files is an important functionality on a Linux machine. Starting with cp, this command takes two arguments:

1. the name of the existing file

2. the name we wish to assign to the new file when copying

cp copies the entire contents of the existing file into the new file. In the screenshot below, we are copying "note" to "note2".

Moving a file takes two arguments, just like the cp command. However, rather than copying and/or creating a new file, mv will merge or modify the second file that we provide as an argument. Not only can you use mv to move a file to a new folder, but you can also use mv to

rename a file or folder. For example, in the screenshot below, we are

renaming the file "note2" to be named "note3". "note3" will now have the

contents of "note2".

Determining File Type

What is often misleading and often catches people out is making presumptions from files as to what their purpose or contents may be. Files usually have what's known as an extension to make this easier. For example, text files usually have an extension of ".txt". But this is not necessary.

So

far, the files we have used in our examples haven't had an extension.

Without knowing the context of why the file is there -- we don't really

know its purpose. Enter the file command. This command takes one argument. For example, we'll use file to confirm whether or not the "note" file in our examples is indeed a text file, like so file note.

How would you create the file named "newnote"?

What are the contents of this file?

Continue to apply your knowledge and practice the commands from this task.

As you would have already found out by now, certain users cannot access certain files or folders. We've previously explored some commands that can be used to determine what access we have and where it leads us.

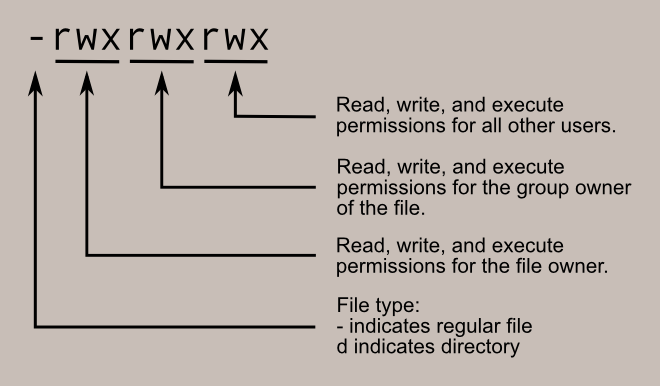

In our previous tasks, we learned how to extend the use of commands through flags and switches. Take, for example, the ls command, which lists the contents of the current directory. When using the -l switch, we can see ten columns such as in the screenshot below. However, we're only interested in the first three columns:

Although intimidating, these three columns are very important in determining certain characteristics of a file or folder and whether or not we have access to it. A file or folder can have a couple of characteristics that determine both what it is that and who we can do with it as -- such as the following:

- Read

- Write

- Execute

The diagram below is a great representation of how these permissions can be translated.

Let's use the "cmnatic.pem" file in our initial screenshot at the top of this task. It has the "-" indicator highlighting that it is a file and then "rw" followed after. This means that only the owner of the file can read and write to this"cmnatic.pem" file but cannot execute it.

Briefly: The Differences Between Users & Groups

We briefly explored this in Linux fundamentals part 1 (namely, the differences between a regular user and a system user). The great thing about Linux is that permissions can be so granular, that whilst a user technically owns a file, if the permissions have been set, then a group of users can also have either the same or a different set of permissions to the exact same file without affecting the file owner itself.

Let's put this into a real-world context; the system user that runs a web server must have permissions to read and write files for an effective web application. However, companies such as web hosting companies will have to want to allow their customers to upload their own files for their website without being the webserver system user -- compromising the security of every other customer.

We'll learn the commands necessary to switch between users below.

Switching Between Users

Switching between users on a Linux install is easy work thanks to the su

command. Unless you are the root user (or using root permissions

through sudo), then you are required to know two things to facilitate

this transition of user accounts:

- The user we wish to switch to

- The user's password

The su

command takes a couple of switches that may be of relevance to you. For

example, executing a command once you log in or specifying a specific

shell to use. I encourage you to read the man page for su to find out more. However, I will cover the -l or --login switch.

Simply, by providing the -l switch to su,

we start a shell that is much more similar to the actual user logging

into the system - we inherit a lot more properties of the new user,

i.e., environment variables and the likes.

For example, when using su to switch to "user2", our new session drops us into our previous user's home directory.

Where now, after using -l, our new session has dropped us into the home directory of "user" automatically.

Now switch to this user "user2" using the password "user2"

Output the contents of "important", what is the flag?

/etc

This root directory is one of the most important root directories on your system. The etc folder (short for etcetera) is a commonplace location to store system files that are used by your operating system.

For example, the sudoers file highlighted in the screenshot below contains a list of the users & groups that have permission to run sudo or a set of commands as the root user.

Also highlighted below are the "passwd" and "shadow" files. These two files are special for Linux as they show how your system stores the passwords for each user in encrypted formatting called sha512.

/var

The "/var" directory, with "var" being short for variable data, is one of the main root folders found on a Linux install. This folder stores data that is frequently accessed or written by services or applications running on the system. For example, log files from running services and applications are written here (/var/log), or other data that is not necessarily associated with a specific user (i.e., databases and the like).

/root

Unlike the /home directory, the /root folder is actually the home for the "root" system user. There isn't anything more to this folder other than just understanding that this is the home directory for the "root" user. But, it is worth a mention as the logical presumption is that this user would have their data in a directory such as "/home/root" by default.

/tmp

This is a unique root directory found on a Linux install. Short for "temporary", the /tmp directory is volatile and is used to store data that is only needed to be accessed once or twice. Similar to the memory on your computer, once the computer is restarted, the contents of this folder are cleared out.

What's useful for us in pentesting is that any user can write to this folder by default. Meaning once we have access to a machine, it serves as a good place to store things like our enumeration scripts.

What is the directory path that would we expect logs to be stored in?

What root directory is similar to how RAM on a computer works?

Name the home directory of the root user

Now apply your learning and navigate through these directories on the deployed Linux machine.

Nice work! This room was quite theory-heavy and covered quite a range of the fundamentals in getting you familiar with Linux. To quickly recap, this room taught you:

- How to connect to a Linux machine remotely using SSH

- Advancing your use of commands by providing flags, switches and where you can go to learn about these for each command (man pages)

- Some more commands that you'll frequently be using to interact with the filesystem and its contents

- A brief introduction to file permissions & switching users

- A summary paragraph of the important root directories on a Ubuntu Linux install and how we may be able to use the data stored within these.

I encourage you to go through this room again once or twice to gain some familiarity with the concepts. After all, practice makes perfect!

Terminate the machine from task 2!

0 Comments